My invention does not meet the patent requirements: when to go for the utility model

When inventors find a new technical solution to a problem, whether a product or a process, traditionally they try to register the Intellectual Property (IP) by going for the patent application as soon as possible.

Registration via this path prohibits others from copying, selling or importing said invention. However, it is often challenging for the inventors to satisfy the patent’s criteria:

- Novelty, the invention must have not been made public yet in any country;

- Inventive step, the solution must not be obvious to an expert in the field;

- Industrial applicability, it must be possible to materialize the invention as it cannot be just an idea.

Due to these preconditions, some solutions cannot be protected via patent, and an alternative should be found for the inventor to keep exclusive rights over the production and commercialization of their creation: customarily, this is the utility model(or similar rights with different names depending on the jurisdiction).

Why is the utility model frequently the best IP protection alternative?

The novelty and inventive step requirements are less demanding or nonexistent for utility models when compared to patents.

Novelty is usually required, but in various countries it is only needed on a local level. In some territories, such as Germany, it is even possible, through a grace period, to register a utility model after the invention has been published.

Regarding the inventive step, it is not compulsory in some jurisdictions, and in others there is at least a less demanding creativity or technical complexity required.

Additionally, utility models are granted much faster than patents, they are not generally examined. This means utility models are also published faster than patent applications, and therefore can be enforced more rapidly in a case of an infringement.

It is also important to note that there are countries that allow the conversion of patent applications into utility models. In some jurisdictions it is even possible to convert a rejected patent into a utility model.

Moreover, utility models are usually more cost effective than patents. If the inventor has a limited budget for the IP, the utility model will be a more realistic option in terms of costs.

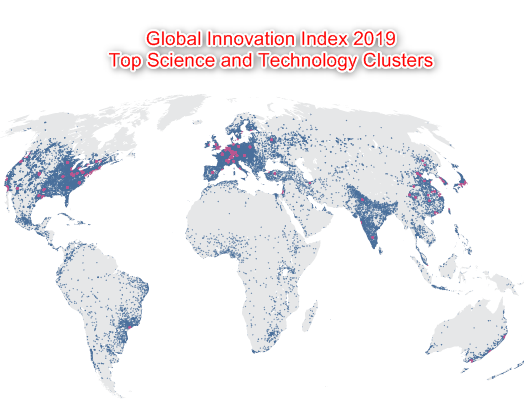

Nonetheless, there are also downsides to the utility models. This IP right exists in interesting markets, such as Brazil, China, Germany and Japan, but there are no utility models or equivalent rights in the United Kingdom or the United States.

Furthermore, the utility model commonly gives protection for between seven and ten years, while patents provide protection for 20 years.

And commercially, and in terms of marketing, it is much more appealing for companies to promote their products or processes as being patented, or as having a patent pending, than as being registered as utility models.

It is crucial to take a strategic approach to the IP rights landscape in the different jurisdictions, and to optimize the dissimilarities among the countries in favor of the inventor. The traditional way is not always the best way.

For more information about utility models, please contact us at info@shipglobalip.com or directly to André Sarmento at asarmento@shipglobalip.com